The emotional brain

Effective fundraising, it seems, is all in the mind. ‘First capture their hearts and minds, then their wallets will follow.’ So my first fundraising mentor, Harold Sumption, founder of the International Fundraising Congress, was fond of saying. What Harold meant was, donors need an emotionally compelling reason to engage, then they’ll seek to reinforce their emotional impulse with a logical justification to give. After that, fundraising is easy. (Equally, prospects can use an emotional reaction to construct a barrier to giving which is nigh impossible to shift.)

- Written by

- Ken Burnett

- Added

- June 02, 2012

Of course Harold’s advice was sound. But we know now that emotions don’t live in the heart– it’s just a pump (though a pretty important one, of course). Emotions invariably are formed in the mind, or more specifically, in certain parts of the brain – several parts – wherein the consciousness that we term the mind evidently resides. From the mind these emotions – fear, anger, stress, elation, anxiety, love and all the rest – can gush out anywhere and everywhere, controlled or otherwise, productively or destructively, far more powerful and irresistible than logic.

The genesis of emotion is always in the mind. There, if we can reach in and unlock them, are emotions that can be stimulated, directed, even created. And, most importantly, there they will be imprinted and retained, like slumbering giants, ready for future activation.

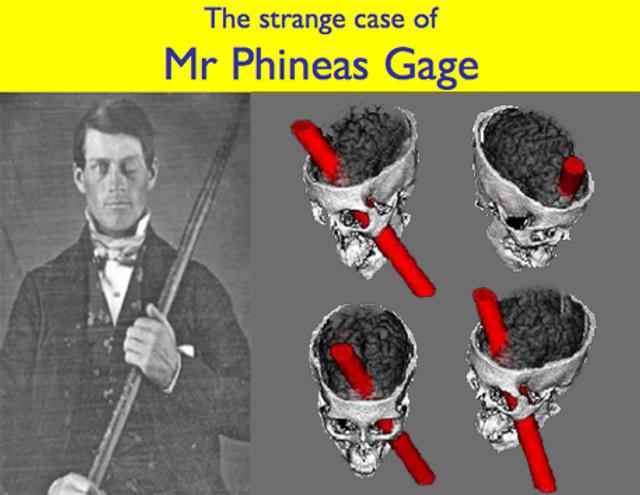

So, I thought it might pay to look further into how the human brain works, to see if anything might emerge that might be of value for fundraisers. That last paragraph is a bit of a give-away – I’ve found a lot, a cornucopia of usable treasure as well as a potential Pandora’s box. For, as we all know, a little knowledge in careless hands can be a dangerous thing. I’ve ploughed through some wearisome tomes and unearthed troves of fascinating facts (such as the startling tale of Phineas Gage, see opposite). And I think I’ve stumbled onto a few real nuggets of gold. It’s these that I’d like to share with you here.

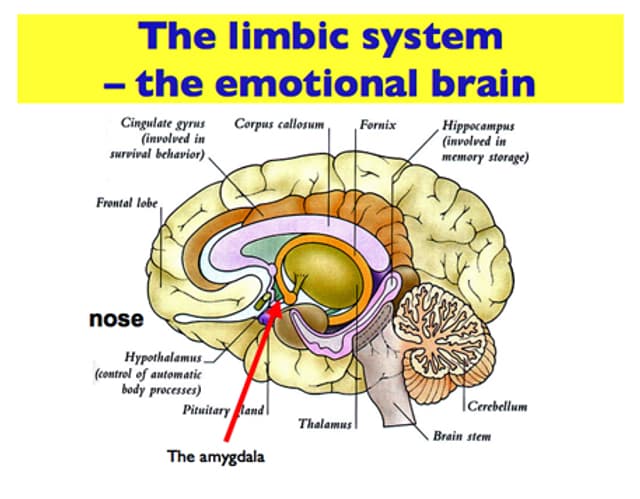

The main ‘controllers’ of emotional memories in our brains are the amygdala and the hippocampus (we have two of each, reflecting the hemispheric nature of the brain). The hippocampus plays a major role in the forming and storing of memories whereas the amygdala is the controller of our emotions (this is something of a simplification, of course; their roles, interconnectedness and relationship with other parts of the brain are still imperfectly understood. And not just by me).

But amygdala and hippocampus are found side by side in their respective hemispheres and seem to work together. American storyteller Tom Ahern picked up on the amygdala recently and wrote,

‘The amygdala is all about fear. It’s your species’ onboard warning system. It tries to make you notice the things that are new in your environment.

‘To the amygdala, ‘new’ represents opportunity. Opportunity to survive. Opportunity to thrive. Your amygdala’s radar asks the same two questions over and over: will it kill me, can I eat it? It notices thenew and dismisses the familiar ... because anything new in the environment could be a potential threat. Or a meal.

‘Tell me something I don’t know? My amygdala tells me to pay attention. Tell me something I already know? My amygdala says I can safely ignore it.’

How many fundraisers are aware of, far less studying, their amygdalas? Or of the hippocampus and its importance in the laying down and retrieval of emotional memories? Maybe we don’t need to know such things, but for sure it’s an area we should watch because there’s much still to learn about the mysterious brain.

In their fairly recent and only partially completed quest to unravel the mysteries of the mind scientists have also come to believe (Antonio Damasio, Descartes’ Error) that mind and body are irretrievably linked. For example, seratonin is a neurotransmitter that regulates our moods, appetite and sleep as well as playing a big part in memory, learning and governing our responses to scarce resources and social dominance. Ninety per cent of all seratonin in humans is found in our stomachs. So gut feeling really does play an important part in regulating our emotions. And emotions, more than anything, drive people’s propensity to become donors (assuming they have disposable income). Emotions have been described as thoughts that produce bodily responses. Though emotions can be of varying intensity, that seems to me to understate their power.

So, which emotions are most likely to affect fundraising, which are most important? And what can fundraisers do to tap into the emotion-producing areas of their donors’ minds, so as to produce unfailingly effective fundraising every time out?

These questions are, perhaps, the most important of all, for fundraisers. The scientists I have borrowed from for answers are, as far as I’m aware, not fundraisers. I’ve not yet come across anyone working as a scientist-fundraiser. Perhaps if we encourage further work in this area some will emerge. There’s much for them to do because the workings of the human brain are still imperfectly understood and, hitherto, most research has been done on animals and even insects. If we still don’t quite get what goes on in the brain of the humble fruit fly it’s a fair conclusion that there’s still more to discover about the human brain.

But we can all aspire to understand the emotional brain better than we do .

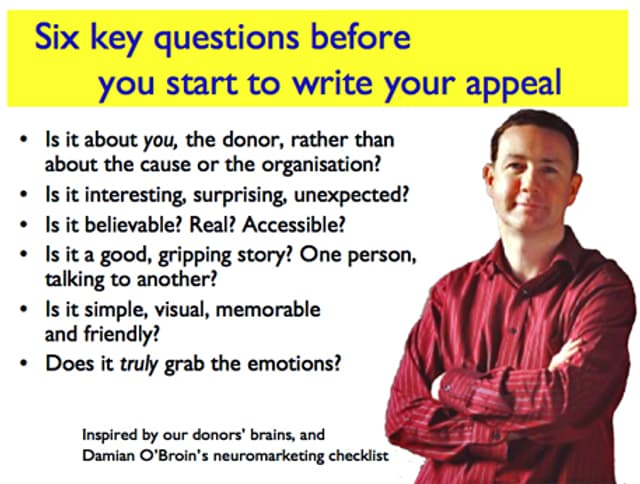

This will give us a range of relatively foolproof ingredients that we can build into our next appeal. In a slide opposite I’ve paraphrased Damian O’Broin from Ask Direct in Dublin who in turn borrowed from Robert Cialdini and others to come up with a brilliant neuromarketing checklist that should be required reading for all fundraisers. You can find it here on SOFII’s blog.

Can fundraising really be so predictably easy? Well, yes, it can, if we understand our donors’ emotional brains and find ways to consistently and indelibly print powerful, emotional, appropriate memories there, to be reactivated later.

First impressions last. Sure they do.

This is a transformational insight, the single biggest realisation of all. It explains things that many fundraisers often feel intuitively but mostly haven’t quite rationalised and that others miss altogether. Such as the surge of emotion when we see a child in distress, the appeal in the direct gaze of a child’s eyes that means all we have to say is, ‘sponsor me’; no more explanation is needed. Or the sweating palms and lump in the throat conjured by the mere image of those soldiers in first world war trenches, waiting for that whistle. Or the recall of time, place and feelings prompted by a piece of music from our past, or by the smell of perfume, or the taste of an exotic fruit. Think Amnesty’s long copy ads, children running from exploding shells, or waiting in food queues at times of famine, or the tired, shocked, dripping lifeboatman just washed in from the sea.

How powerful are the emotions conjured by images such as these? How useful would it be to consistently harness them to your cause? Well, the emotional scenes are already there or they can be planted there to be called upon later, if only we get better at emotional storytelling, at presenting our emotional case with power and passion that will burn the memory of our story so deep that it will last and last long term, to be called upon again and again, whenever needed.

We should study the brain to learn how we can skillfully, sensitively and carefully exploit its potential to store emotional memories that we can access, later, when we have use for them.

I rest my case. At least, for a while.

More reasons why fundraisers should study the emotional brain.

Phineas Gage was clearing rocks for the US railroad in 1848 when dynamite he’d just placed in a hole was accidentally fired. The heavy metal pole he’s seen holding rocketed through his skull leaving a two-inch tunnel diagonally through his head, tearing away his pre-frontal lobe. Amazingly he not only lived, he sat up beside the buggy driver who took him to the nearest doctor, chatting away. More than 100 years passed before scientists realised that Phineas Gage had been living proof that brain and mind are connected but are not single entities. Instead they’re made of several different compartments all with distinct and separate functions. We should know that.

We just have to glimpse those lines of scared, silent men waiting to go over the top for a flood of emotions to pour in. In the midst of the final hilarious episode from the comedy seriesBlackadder viewers are skilfully, effortlessly and wordlessly reminded just how unfunny that final scene was.

Ken’s book Storytelling can change the world, which discusses how we appeal to the emotional brain, is reviewed here.